Early this year, 2020, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the cause of the disease called COVID-19, which has spread globally in a pandemic that has created a worldwide emergency. The symptoms of the disease are fever, fatigue, muscle pain, diarrhoea, and pneumonia and the levels of severity vary, with most infected individuals experiencing mild symptoms that do not require hospitalisation, while other individuals, especially the elderly and those with risk factors, experience severe illness that can even be fatal.

In recent months and in the absence of a vaccine, many studies have been focusing on the immunisation that occurs through contact with the disease, especially in asymptomatic cases or those with very mild symptoms. Although the immune response mediated by antibody-producing B lymphocytes, known as humoral immunity, has been the most widely studied to date, we know that it is not the only response generated, but that there is also cellular immunity, which is the response of our immune system through T lymphocytes.

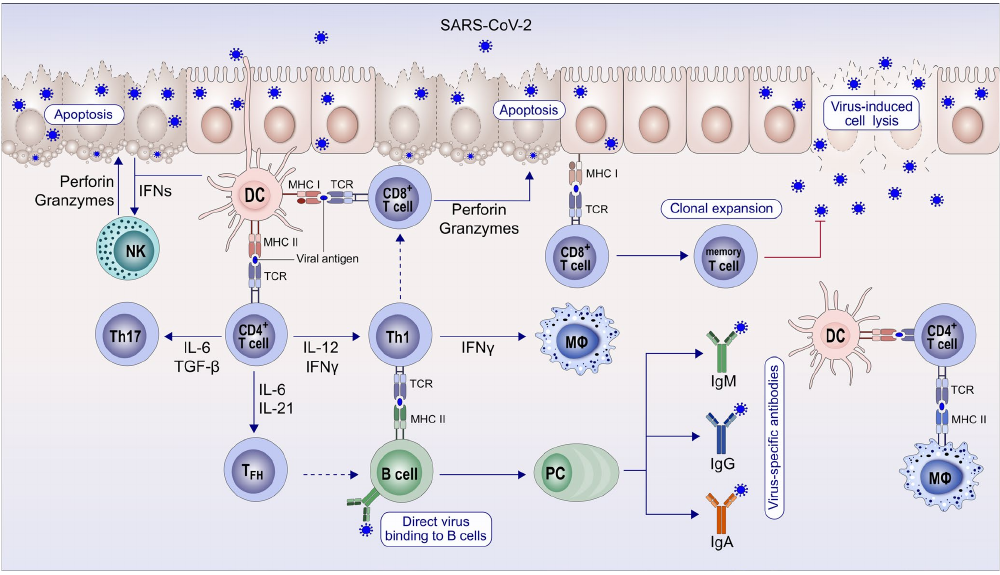

When the virus enters our body, antigen-presenting cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) bring it into contact with the lymphocytes and a response is initiated: the activation of B-lymphocytes, which begin to produce antibodies (humoral response), and of cytotoxic TCD8+ lymphocytes, which are able to distinguish infected cells from healthy ones, destroying only the former. Once the acute phase of the disease is over, the response is broader and memory lymphocytes are produced to provide long-term protection.

It has been proved that antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are not detected in all patients, but that it is frequent not to find them in patients with mild cases of COVID-19. Moreover, this B-lymphocyte-mediated response is limited, and antibodies may disappear over time. However, the T-cell response lasts longer and allows a rapid response to be generated in the event of a second contact with the virus.

In recent studies, SARS-CoV-2 reactive T-cells have been identified. In addition, these cells have been identified not only in patients with severe cases of COVID-19, but also in those with mild or asymptomatic cases who have been exposed to the virus (patients’ relatives) and, more surprisingly, in healthy donors who have not undergone any exposure. This finding suggests that a certain degree of immunity can be acquired probably due to contact with other coronaviruses that cause the common cold, meaning that part of the population has a “basic” protection in the event of exposure to the virus that allows them not to develop the disease or to experience milder clinical symptoms.

Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azhur D, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy, 2020; 75:1564-1581. http://doi.org/10.1111/all14364.

The presence of reactive T-cells has been studied in convalescents with negative results in the serological test, being detected in 41% of cases. In the case of people with positive results in the serological test, the percentage of convalescents with specific T-cells against SARS-CoV-2 is 99%. This means that, although the majority of those infected generate both humoral and cellular immunity, there is a proportion of those infected that would only generate cellular immunity, with a greater proportion of the population being protected than shown by the serological tests.

It is important to point out that it is not possible to assess cellular immunity in the general population in the same way as humoral immunity, since in order to assess the latter, there are widely distributed commercial antibody tests, which are easy to perform and interpret, while in order to assess cellular response, it is necessary to carry out cell cultures, cell activation with specific antigens of the virus and assessment of the activated cells using complex techniques, so this type of immunity is only being assessed in research studies.

Although further studies will be necessary to reach firm conclusions, it is already possible to suggest that the variability of symptoms among patients or the chances of developing serious disease may be related to cell-based immunity, among other factors, and that cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses may be a protective factor against SARS-Cov-2. Therefore, it is not only important to have generated antibodies, but to have generated a memory T-cell response that is able to trigger a rapid response in the event of reinfection. And in order to develop a vaccine, it is necessary to take into account this branch of the immune response, which provides the long-term “memory”.

AUTHOR: Julia Illán Ramos • Head of Flow Cytometry • Analiza Sociedad de Diagnóstico

—

Español

Español Português

Português

¿Quieres recibir noticias como ésta en tu email?

Suscríbete a la newsletter